Episode 15: The Wonders of the East, Pt 2.

- Zoe Franznick

- Mar 8, 2021

- 8 min read

Updated: Mar 11, 2021

We're back with our guest, Mary Osborne of BookSquadGoals, to continue our tour of the furthest reaches of the medieval world. The bizarre illustrations continue, and we're all pleasantly surprised at how inclusive this text is in regards to what sort of races count as "people."

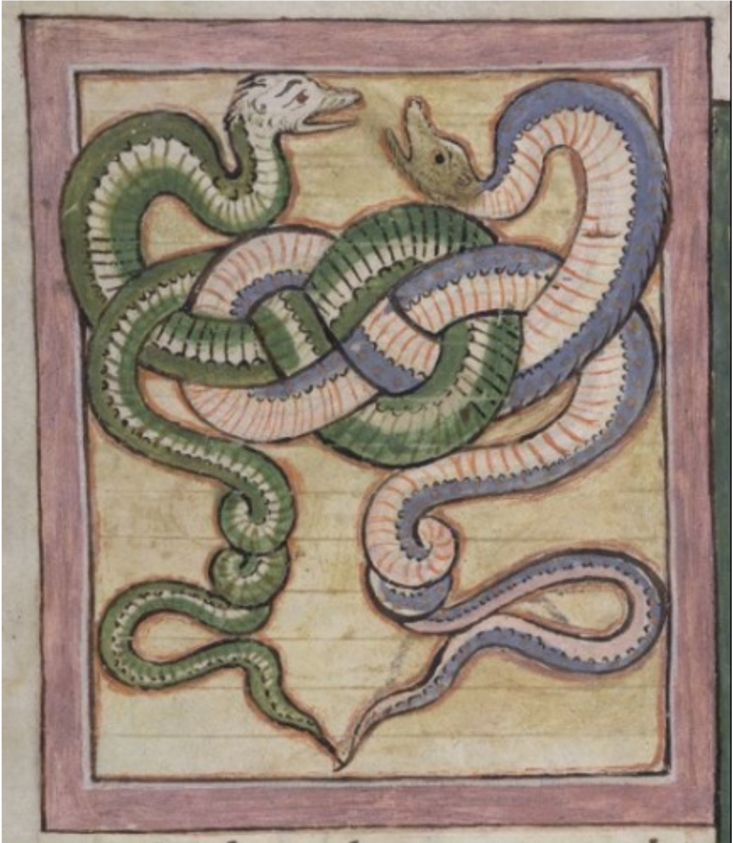

We covered the background of this text in Part One of the Wonders of the East, which you can read here. To sum it up, The Wonders is an eleventh century work of Old English which describes the various peoples, lands, and creatures found in "the east" - i.e. anywhere east or south of the Mediterranean Sea. The work is found in both the Nowell Codex and the Tiberius manuscript. Each contains illustrations of the corresponding entry, though each illustrator has taken some liberties in his art style. With that in mind, let's dive back in!

We're picking back up in Locotheo, near the Nile and Brixon rivers, where there live extraordinarily pale people who are 50 feet tall. These folks have red knees black hair, and two noses (notably, both illustrations expand this so that these people have two faces). The text also notes that when these people wish to give birth, they leave their land and go to India.

Next, in Gaul (modern-day France), there is a land called Ciconia, or Liconia, in which tri-colored men are born. These people have the manes of lions and are twenty feet tall. Despite their impressive size, they flee from the sight of foreigners and sweat blood when they are frightened.

Beyond the Brixon River are the Hostes people, who have feet and shanks twelve feet long and chests seven feet long. Given that they are described as cannibals, it is no wonder the text calls them hostes, which is the Latin for "enemy."

On an island in the Brixon live creatures called Lertices. The text only briefly describes these beasts as having the ears of asses, wool of a sheep, and the feet of a bird. We wager they might be a close relative of the griffon.

On another Brixonte island live the "headless men," also known as akephaloi in the Greek or blemmyae in the Latin. These people are eight feet squared - literally. Their faces are on their chests, giving them a rather boxy figure.

The text next pauses to mention the multitude of dragons in this area, which make it difficult to travel. These dragons are about 150 feet long, or "about as long as a stone pillar."

Returning to the main body of the work, the scribe mentions a place south of the sea where onocentaurs live. The text calls these creatures "homodubii," but since we have an earlier report of those people and since we have clear depictions of onocentaurs elsewhere, it is obvious this was a scribal error. These onocentaurs are half-man, half-donkey, have soft voices, and flee if they see people.

Next come a "barbarous people" who have 110 kings. The text says little about them, but notes that they have two lakes: one of the sun and one of the moon. During the day, the sun lake is hot and the moon lake is cold, while at night, the sun lake is chilled and the moon lake warm. The balsam tree also grows here, akin to the laurel and olive trees.

The text follows by describing the Donestre, who live on an island in the Red Sea. These creatures are "like soothsayers to their naval" while their lower halves are human. The Donestre know all human languages, and attempt to lure people to their island by calling their names before devouring them. Notably, Asa Simon Mittman notes that the "soothsayer" element was listed as frifteras in the Old English, and might be a mistranslation of the Old English frettan, meaning "to eat, or devour." This would certainly account for their choice of meal.

East of there are people fifty feet tall and ten feet wide, who have long, white ears down to their feet. According to The Wonders, they use their ears as a bedroll and blanket. If they see another person, they grasp each ear in hand and flee. The flapping of their ears makes it seem they are flying.

Located on another island, the following people have only a brief description, but their curious illustration makes up for it! These unnamed folk have eyes which glow as bright as lanterns.

On a different island about 110 miles around, there is an ancient temple built in the days of Job. The descriptions of this temple vary: the Tiberius manuscript says it is made of brass, while Nowell says it is made of molten glass. The texts continue to diverge - Tiberius says that to the east of this place is another temple dedicated to the sun where lives a priest, while Nowell continues to describe the same temple and its bishop, Quietus, who lives exclusively on raw oysters.

Following this entry is mention of a vineyard in which grows berries 150 feet across and are full of pearls and gemstones. Quite the find, if we only knew where this vineyard was located.

The text then mentions another kingdom in the land of Babylon where the largest and highest mountains between those of the Medes and Armenia. Decent men rule there all the way to the sea. Near this land are also women who have beards. They wear horse hide and train tigers and leopards who hunt with them.

There are other women in this area who have camel's feet, the tusks of boars, ox-like tails, and hair down to their heels. These women are described as fierce, but were killed by Alexander when he could not conquer them. These creatures are likely fauns or saytrs, and are mythological cousins to the Scandinavian huldra.

The text is not sure whether the following folk are really people. The Cetini are described as beautiful, but live on raw flesh and honey. A strange diet, to be sure.

In this land also live a variety of "hospitable men," whose kingdoms stretch all the way to the sea. Close to this land there are many people whose is custom in their land that if a stranger should visit, he should be given a woman before he departs. According to the text, Alexander the Great "wondered at their humanity." We neither agree nor endorse Alexander's definition of "humanity" here.

Similar to the large berries earlier, the text mentions a similar tree which grows gemstones rather than fruit. We really do wish the scribe gave us more place-names in his travel guide.

The final people that the work mentions are folk who are black-skinned. The text here is especially fascinating because the Old English word varies between manuscripts: Tiberius uses silhearwan, while Nowell uses sigelwara (the Latin uses Etheopianis). J. R. R. Tolkien wrote a two-part article (linked in references below) about this word. Ultimately, he comes to little conclusion except that later scribes used it to mean "sun dwellers."

The Nowell codex ends here, but Tiberius ends with a few more entries more familiar to modern readers. The first is that of the griffon, who lives on Mount Adamans, with the second, a phoenix. The griffon has the hindquarters of a horse, head of an eagle, and legs of a bird. The phoenix has a comb on its head like a cock, and lives in a nest of cinnamon. After 1,000 years, the phoenix lights itself on fire and is reborn from the ashes.

The final entry in the Tiberius manuscript is that of a group of "black people" whom no one else can visit because the mountain upon which they live is constantly aflame. We lack any illustration for this entry.

There are a few particular notes to make about this text. The first is its relative inclusivity! In a world where many individuals were not considered "people," such as witches (or other single women), Muslims, Jews (who were expelled from England in 1290), or even the Irish (who were considered quasi-human during English colonization). The Wonders of the East is not without flaws, and it may be uncomfortable for a modern audience to hear "Ethiopians" listed alongside creatures such as onocentaurs or lion-headed men, but it is important to remember that a reader in early medieval England at that time would likely believe each and every one of these creatures existed. They had neither the resources nor the ability to fact-check these assertions. For the text to include even the "homodubii" as a group of people despite the obvious doubt in their name demonstrates the inclusivity and tolerance of this text.

Another interesting note about this text is the illustration work! As Mary pointed out in the episode, comic and writer Scott McCloud hearkens the origin of comic books to the art of the middle ages, including illuminated manuscripts. The scribe's willingness to "break" convention by allowing his subject to grab the frame or otherwise interrupt the fourth wall demonstrates the creativity of the medieval artist. Before artistic convention became highly formalized during the Renaissance, medieval scribes often had fun doodling in the margins of their books or throwing in small details to their illustrations for added flair and humor.

Don't forget to check out our segment sections for more discussion and ideas for your writing, tabletop games, or academic work! Stay tuned for our final installment as we finish The Wonders of the East!

Thanks for joining us in this week's episode of The Maniculum Podcast. Looking for more? Check out our Master List series for the full collection of segments at the end of our show, and for more gaming and world building ideas, check out The Gaming Table section of our blog, Marginalia!

Searching for our sources? Look at The Wonders of the East manuscript here, and check out our Library for more! The Nowell Codex can also be seen in full here, and the Cotton Tiberius B V manuscript is available here. Mary also mentioned a song with the Mellified Man, which you can listen to here.

Additional references for interested scholars:

Frembgen, Jurgen W. "The Magicality of the Hyena: Beliefs and Practices in West and South Asia". Asian Folklore Studies, 57, 1998, 331–44. Link.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: the Invisible Art. Tundra, 1993. Link.

Pliny the Elder. Natural History. Trans. John Bostock. Project Gutenberg. Link.

Tolkien, J. R. R. “Sigelwara Land.” Medium Ævum, vol. 1, no. 3, 1932, pp. 183–196. Link.

Tolkien, J. R. R. “Sigelwara Land. (Continued).” Medium Ævum, vol. 3, no. 2, 1934, pp. 95–111. Link.

Thomson, Simon. "The two Artists of the Nowell Codex 'Wonders of the East'." SELIM: Journal of the Spanish Society for Medieval English Language and Literature. 21, 2016, 105-54.

We do our best to accurately research, source, and cite the works we use, and make them available to you, too! Each episode has a corresponding blog post which includes further breakdowns of the big ideas in each text as well as cites our sources and references. We also have the Maniculum Library, which actively collects resources and recommendations for writers, scholars, and geeks alike! We update our collection of Master Lists after each new episode, so be sure subscribe and stay updated!

Are we missing something? Let us know! We'd love to add more knowledge to our ever-growing compendium. Chat with us on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook.

Thanks for checking us out! If you like our content, please share it! If you want to support us, rate and review on iTunes, find us on Patreon, or buy us a coffee so we can keep making content you love.

"it is important to remember that a reader in early medieval England at that time would likely believe each and every one of these creatures existed." Why 'likely'? I know there was academic discourse in the middle ages about whether kynokephali could be saved through baptism (See St Christopher myths and Paul the Deacon), but I generally think most people were probably as cynical/gullible as people today...